In 2017, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) introduced a requirement for annual advisory resolutions on executive remuneration to be tabled. This has placed it firmly in the spotlight for shareholders and stakeholders alike. As Nicole Hamman explains, inspecting how the top decision-makers are incentivised to act and think has always been part of the investment case. When executive pay is closely aligned with performance, executives are more likely to make value-accretive decisions and less inclined to pursue actions that erode value, ultimately preserving, and creating shareholder value on behalf of our clients.

Over time, executive remuneration structures have become increasingly complex. In theory, it should be simple. Executive incentives are usually delivered through two instruments: a short-term incentive (STI) and a long-term incentive (LTI). Both should be tied to performance conditions that reflect the short- and long-term value drivers of the business. Naturally, these performance indicators will differ by industry, as the value drivers for a mining company are not the same as those for a healthcare provider. How complex can it be?

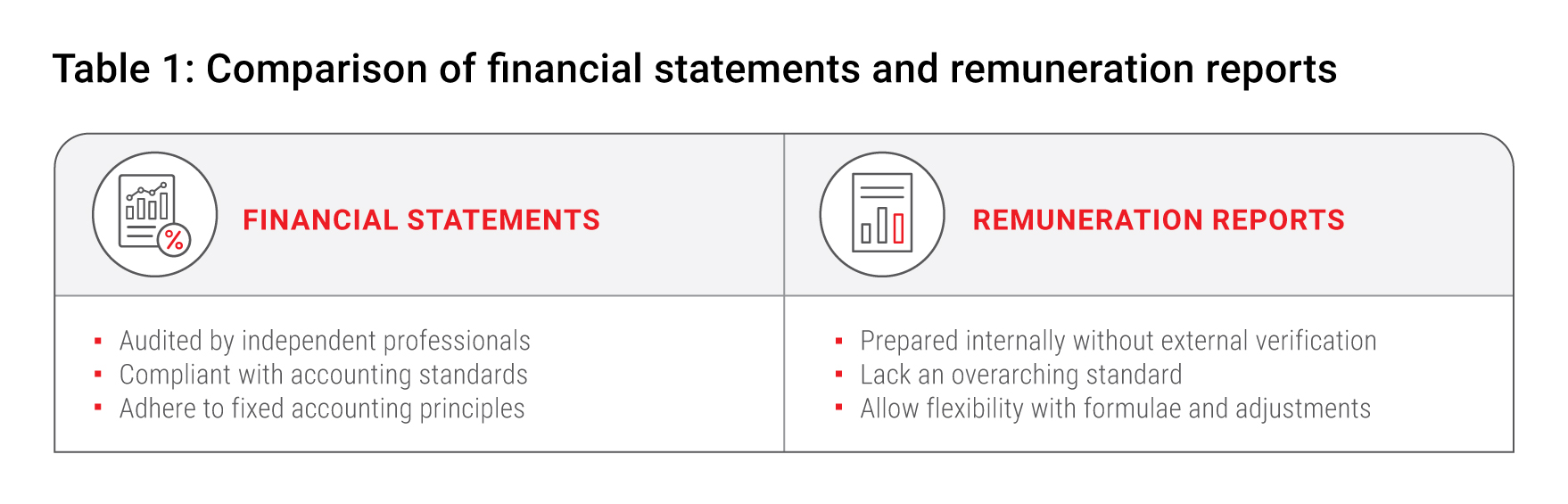

Financial statements are prepared in line with established standards, such as International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) or Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), which provide a robust framework for consistency and comparability. External assurance is provided according to the applicable standard. In stark contrast to this, there is no overarching standard for remuneration reports that ensures consistency or comparability, as demonstrated in Table 1 below.

We do have the King IV Report on Corporate Governance™ for South Africa, which includes disclosure requirements, but these are recommended practices. While King IV provides some standardisation for the broader elements of remuneration, there is a growing lack of consistency and transparency when it comes to adjustments for remuneration purposes, the formulae used for performance metrics, and the methodologies applied. We explore these issues with reference to an LTI with three performance metrics: earnings per share (EPS), return on invested capital (ROIC), and total shareholder return (TSR).

Overly adjusted performance

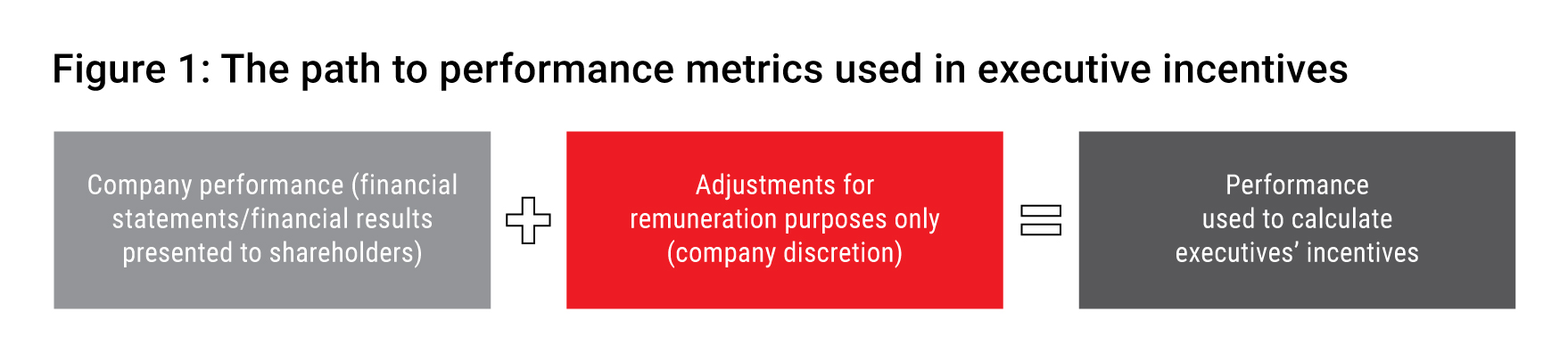

Ideally, and as is the case for many companies, there should be no middle block in Figure 1, meaning no difference between the performance presented in the financial results to shareholders and the metrics used to measure executives’ performance. For example, the EPS metric should align with either the IFRS basic or diluted EPS figure, or the JSE-mandated headline EPS metrics, which further exclude certain non-recurring and non-core items from the IFRS figure, as per established guidelines.

However, in some cases, companies go beyond these established adjustments and apply additional adjustments to these metrics specifically for remuneration purposes, removing what they consider to be factors outside management’s control. While reasonable in theory, this extra layer of adjustments opens a realm of subjectivity, which, if left unchecked, can seriously distort performance used to assess executive pay from the true performance of the business.

Below are examples of additional adjustments we have observed, which highlight the inconsistencies and risks associated with these practices:

- A retailer added back the cost of loadshedding to their earnings metric, while peers operating in the same environment did not.

- A telecommunications company excluded the cost of an IT-related project in the short term, even though such projects represent business-as-usual costs for a technology-driven business.

- A company removed the effect of its loss-making division from its group earnings metric, because, at the time of the award, the division was not part of the business. There was no divisional incentive.

Risk of discretionary adjustments

Management’s role includes effective capital allocation and avoiding unnecessary or wasteful expenditure. It is a very slippery slope to carve out certain costs when evaluating executives’ performance. Robust STI and LTI structures should work in tandem; there should be no need to adjust the STIs for investment decisions made today with an uncertain outcome. If these investments prove successful, executives will be appropriately rewarded through their LTIs. Adjustments in LTI calculations are rarely warranted, given that LTIs span at least three years and are designed to smooth out short-term anomalies.

Importantly, adjustments to executive remuneration are often proposed by management, as they possess the deepest operational understanding of the business, unlike non-executive directors. In practice, management (executives or those ultimately reporting to executives) recommends these adjustments to the remuneration committee (remco). However, this process presents an inherent conflict of interest, as management has a strong incentive to propose favourable adjustments to their own remuneration. This contrasts with the broader remuneration process, where independent remuneration consultants and external benchmarking provide remco with insights into industry standards and reasonable pay structures.

In some cases, adjustments to performance metrics are substantial and consistently favourable to management. This creates a murky starting point in evaluating remuneration outcomes, as shareholders base their assessment of management’s performance on the financial results reported to them, while the remco (and potentially management themselves) perceives a much rosier picture, leading to unwarranted pay outcomes.

Lack of disclosure and transparency

Compounding the issue is that there is no requirement for companies to disclose these adjustments or provide a reconciliation between company performance metrics and those used for remuneration purposes. For example, a reconciliation is required by the JSE Listings Requirements between the IFRS EPS metric and the headline EPS metric, ensuring transparency in financial reporting. However, when headline earnings are further adjusted for remuneration purposes, no such reconciliation is typically provided, leaving shareholders in the dark about how these adjustments impact reported performance versus remuneration outcome.

Understanding the formulae

There is no standardisation in how companies define their performance metrics. ROIC, a common metric for miners, is typically calculated as net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) divided by invested capital (i.e. the net assets used to generate that NOPAT). Impairments – generally a consequence of poor historical decisions or declining asset values – reduce both the numerator and denominator (invested capital) in the year that they are first recognised. However, impairments’ impact on the denominator is typically permanent, which can inflate ROIC in subsequent periods. We think this is misleading, as it only creates the appearance of higher efficiency on account of the erosion of underlying asset value. We therefore critically evaluate how miners account for asset impairments, as we do not want management to unfairly benefit from an inflated ROIC that is predominantly driven by past impairments.

Similar nuances arise in other metrics, such as return on capital employed (ROCE), where accelerated amortisation of intangible assets can distort the capital efficiency for intangible-heavy businesses. In many cases, there are various formulae for the same metric, and the most appropriate one depends on the company’s unique positioning. For example, there is no standard definition of free cash flow (FCF). Some definitions include only maintenance capital expenditure (capex), while others include both maintenance and expansion capex. It would be concerning if a miner that is pursuing an aggressive growth or exploration project excluded expansion capex from its FCF metric (i.e. overstating FCF generation) without a separate performance metric that accounts for the increased expenditure.

There is no requirement for companies to disclose the formulae used for remuneration metrics. However, we believe that this transparency is essential for both remco and shareholders as nuances in calculations can incentivise the wrong behaviour.

Inconsistent methodologies

The examples cited are quite company-specific, and we can see how there are discrepancies on implementation. Conversely, we also find inconsistent methodologies for what are well-defined industry metrics. For example, TSR is an external, readily available metric from third-party providers. There is consensus on its methodology of including share price appreciation and dividends. However, over the years, we have seen company-specific definitions of this widely understood metric.

Recently, a company presented the metric as TSR relative to the FTSE/JSE All Share Index, but on implementation, the actual results did not reconcile with our recalculation. The company justified its approach of comparing only price returns by stating that it is currently a non-dividend-paying company and that this aligns with the expectations of its investors. We strongly opposed this approach, as it undermines the purpose of TSR as a total return metric. The investment universe includes both dividend-paying and non-dividend-paying companies; TSR must account for dividends to allow for a true comparable measure. In this example, the company’s total return did not meet its target to warrant performance-based pay. However, by using only the price return, executives met the target and earned significant performance-based pay.

This illustrates the extent of the discretion available as even a metric that is well defined in the industry can be altered for remuneration purposes. We strongly question the remco oversight in instances like these.

The importance of remco members

Previously, the relationship between shareholders and remco members was more direct, with both parties needing to be well informed. However, like many aspects of ESG, the landscape has expanded rapidly with new service providers entering the space.

Most large issuers now make use of external remuneration consultants to advise remco. These consultants, paid by the company, have no duty to shareholders or other stakeholders. Some asset managers rely on proxy advisers instead of conducting detailed remuneration assessments. These advisers, the largest of which are global firms, tend to adopt a rules-based approach given their scale, which is one of the reasons we do not use them.

Over time, possibly due to the growing complexity of executive remuneration and increased reliance on consultants, we have found some remco members to be less familiar with critical details such as formulae, adjustments and methodologies. As shareholders, we can raise our concerns on implementation (often when these issues first become apparent), but it is arguably too late to effect meaningful change, as the payouts have been made.

This underscores why we were opposed to the highly punitive consequences for remco members proposed in the Companies Amendment Bill. We believe this could paradoxically discourage strong board members from serving on remcos, whereas a robust remuneration scheme is built on a strong and informed remco that asks the right questions before outcomes are finalised.

Going forward

We do not believe that external assurance is necessary for remuneration reports, as there is no formal standard to provide a meaningful basis for assurance. In fact, many of the flawed formulae and adjustments we have highlighted were verified by independent remuneration consultants. The issue is not whether adjustments are calculated correctly, but whether they should have been made at all. Similarly, it is not whether a formula is applied correctly, but whether that formula incentivises the right behaviour.

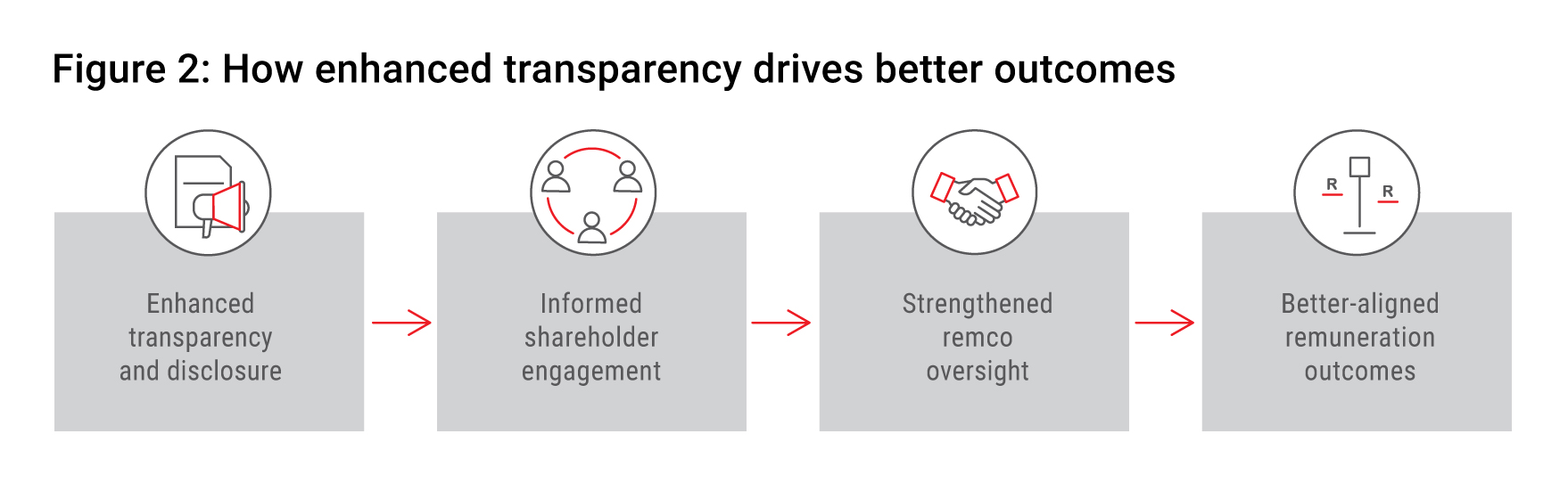

Enhanced transparency would allow shareholders to identify their concerns earlier, rather than only detecting issues on implementation when payouts have already been made. We recommend the following:

- The clear definition of performance metrics.

- Disclosure of the historical results of these performance metrics. Many companies provide financial overviews in their integrated reports (spanning five or 10 years), and these could easily include key performance metrics used for remuneration.

- The clear outlining of any adjustment made to these performance metrics.

We encourage remco members to engage deeply with the details, as that is where the wheels come off. They should have a clear understanding of how performance metrics are calculated and critically assess the necessity and fairness of any adjustment. When the above-mentioned three points are not disclosed, it means the remco is not the last line of defence against poor remuneration outcomes, but the only defence. Enhancing disclosure and meaningful shareholder engagement can shift that dynamic by strengthening the additional oversight that shareholders can provide, creating a more robust system, as shown in Figure 2 below.

With the remuneration-related amendments in the Companies Amendment Act awaiting an effective date, meaningful shareholder engagement is at risk. We encourage companies to continue with annual shareholder engagement on executive remuneration, regardless of their level of shareholder support. Ongoing and quality shareholder engagement is critical in ensuring that the key details that play an influential role in aligning incentives with desired behaviour are not overlooked.

For more information about how we consider ESG factors as part of our investment process, please consult our latest Stewardship Report.